The number of things I have left to do on my to-do list for Everest seems to be perpetually telescoping outwards as I begin the transition from simply training for the mountain to both training and planning for it. At times it’s felt overwhelming; how do I prioritize what needs to get done when everything feels like a priority? There are now over 250 items (and counting) on my to-do list, and some of them need to get done before I head to Boulder next week. What needs to get taken care of now, and what can safely get put off to a later date?

To manage this workload I turned to my old standby, Microsoft Excel, to organize and structure my tasks. I know there is better task management software out there, and I know many folks in the aerospace industry swear by Jira, but Excel is what I have on hand and I don’t have to learn anything new to use it.

To organize my priorities for purchasing, modifying, and fixing my gear, I’ve compiled the entire gear list sent to me by my guide company in one column, and then created five additional columns to describe several different categories related to the gear.

The first column identifies the item’s criticality: do I need it to survive on the mountain? On most peaks, the answer for each piece of gear is almost invariably yes: as weight-critical as this sport is, each piece of equipment needs to serve a physiologicalor mission-specific purpose; otherwise it’s left behind. Everest is a slightly different beast; because yaks and porters12 are available to ferry equipment up to base camp, I’m allotting myself a few luxuries I normally wouldn’t bring with me on a mountain: an iPad to watch movies, for example, or a ukulele to annoy my teammates with. These items serve more as psychological aids for the long, drawn-out periods at base camp spent acclimatizing, which, while not trivial, are typically the first to be left behind in a climber’s never-ending quest to cut weight.

I’ve categorized a piece of equipment as a 3 if it’s required to summit; a 2 if it’s serving as a backup; and a 1 if it’s serving as a luxury:

The second column describes an items availability. Do I have the piece of gear already? Or is it a long-lead item that will take time to arrive from overseas? Items like my down suit and my 8000m boots, for example, fall in to the latter because they are highly specific and thus much harder to come by than most pieces of mountaineering equipment.

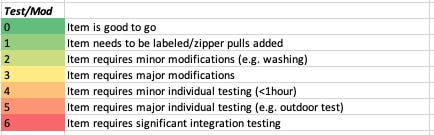

The third column is testing and modification. Is the gear good as is, or do I need to make minor or major changes to it? If it’s the latter two, do I need to test it on its own or in conjunction with other pieces of gear? For example, if I purchase a new pair of mittens, I’m going to want to test them outside to verify they keep my hands warm, they work well with my inner liners, and they have sufficient dexterity to allow me to clip and unclip carabiners, open water bottles, etc. Mittens therefore get labeled as a “6: Item requires significant integration testing.”

The fourth and final category is backup. If I don’t already own the piece of gear, do I have something similar that could work in a pinch? If so, then I can worry a bit less about preparing that piece of equipment.

I then use the following formula to generate a total score for each piece of gear:

total score = [criticality x (availability + testing and modification)] - backupThe higher the gear’s score, the higher I prioritize resolving any issues with it.

Now I know what your going to ask: Did I just spend an entire morning building a spreadsheet (to say nothing about writing a blog post about it) when I might have better spent my time purchasing, fixing, and sorting all this gear? Sure, maybe. But I’ve spent the last three days doing the latter, running around my parents’ house like a chicken with its head off, and I’ve felt nothing but anxiety in the process: when you don’t have a sense of your priorities, it’s easy to imagine a monster of a difficult-to-finish task lurking around every corner.

So instead I’m sticking with the spreadsheet. I can afford to be smart about this now because there’s no reason to be stupid. Not here at home planning and certainly not high on the mountain—where the real monsters live.

I don’t want to sound as though I’m being dismissive of the porters and Sherpas here, as they will be doing the backbreaking, thankless task of ferrying food, tents, oxygen, etc. to our high camps and doing the dangerous work of fixing lines. But it’s for that very reason that I refuse to toss in something trivial for them to carry, even if it might be psychologically beneficial to me.

There’s also the issue of animal cruelty here that I don’t want to be dismissive of either. But the truth is if I were to try and ferry all my gear from when I step off the plane in Lukla all the way to base camp, I’d never get there in time to summit and I’d be so worn down I doubt I’d even try. So a big shout-out and thank you to the yaks too; I know you’d much rather be doing something else.